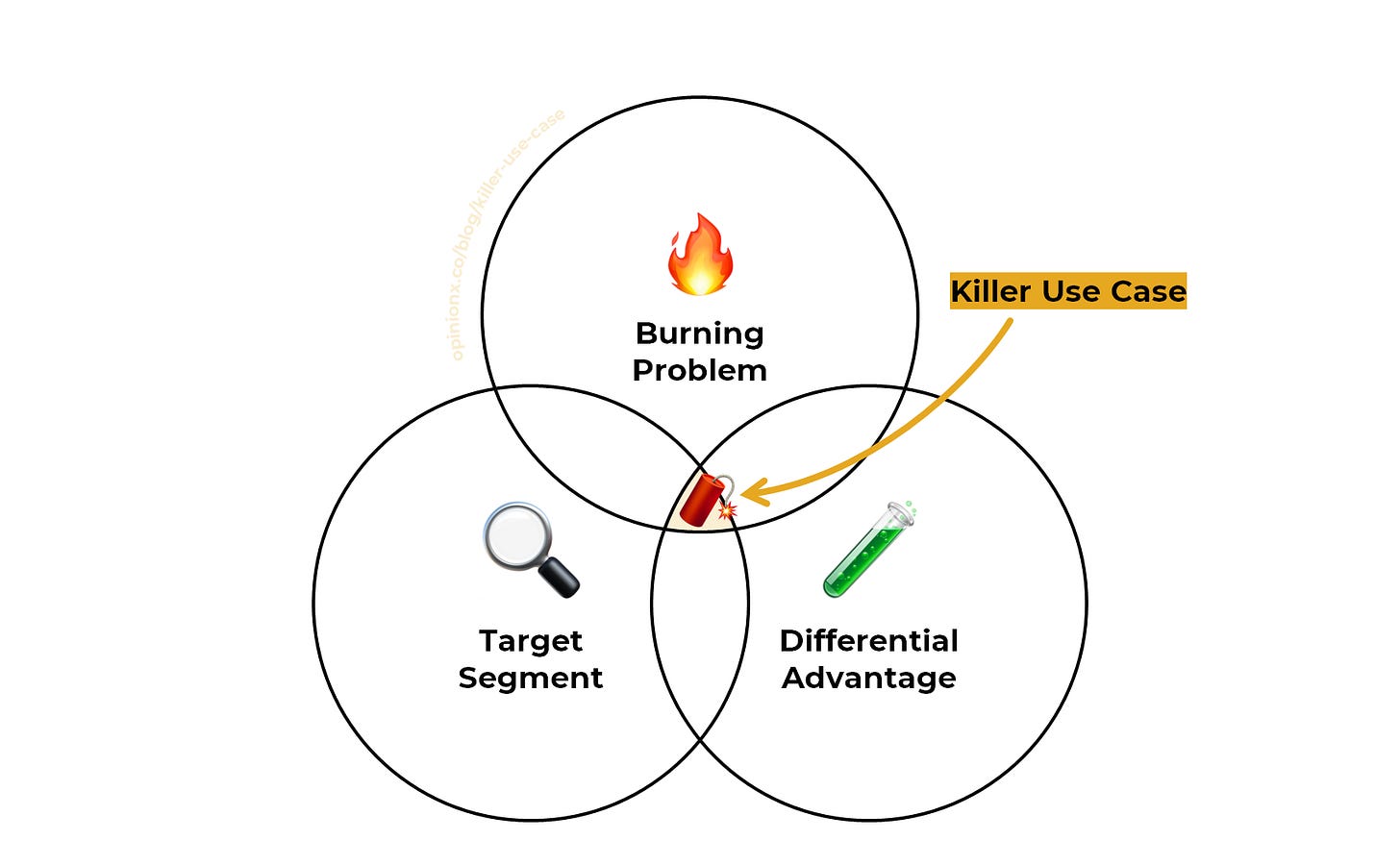

One Killer Use Case Beats 10 Mediocre Ones

The Strategic Power of Focused Value Creation

In the relentless pursuit of market dominance, businesses often fall into the trap of casting the widest possible net, believing that addressing multiple use cases simultaneously will maximise their chances of success.

This scattershot approach, while seemingly logical, frequently leads to mediocre solutions that fail to deeply resonate with any particular audience.

The counterintuitive truth that emerges from studying successful companies is that one killer use case - executed with surgical precision - consistently outperforms a dozen mediocre attempts at solving various problems.

The Psychology of Essential Solutions

The concept of becoming essential for a specific pain point taps into fundamental human psychology.

When individuals or organisations encounter a problem that causes genuine friction in their daily operations, they don't merely want a solution - they crave relief.

This distinction between wanting and craving represents the difference between a nice-to-have feature and an indispensable tool that users cannot imagine living without.

Research in behavioural economics reveals that people experience loss aversion at a ratio of approximately 2:1, meaning the pain of losing something is twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining something equivalent.

When a product becomes essential for solving a critical pain point, removing it creates a disproportionate sense of loss.

This psychological phenomenon explains why companies that achieve deep penetration in solving one specific problem often enjoy remarkable customer loyalty and resistance to competitive threats.

The neuroscience of decision-making further illuminates why focused solutions succeed.

The human brain, when faced with cognitive overload from too many options or unclear value propositions, defaults to the status quo or the simplest available choice.

A product that clearly and powerfully addresses one specific pain point reduces cognitive burden and creates what psychologists call "cognitive ease" - a mental state that increases the likelihood of adoption and continued use.

Source : OpinionX

The Compounding Nature of Focused Excellence

When organisations concentrate their resources on perfecting one use case, they unlock compound returns that are impossible to achieve through diversified efforts.

This concentration creates several mutually reinforcing advantages that build upon each other over time.

First, focused development allows for deeper understanding of user behaviour patterns.

Teams can invest in comprehensive user research, studying not just what users do, but why they do it, when they encounter friction, and how their workflows evolve over time.

This granular understanding enables the creation of solutions that anticipate user needs rather than merely responding to them.

Second, concentrated efforts lead to superior technical execution.

When engineering resources aren't spread across multiple disparate features, developers can optimise for performance, reliability, and user experience in ways that broad-spectrum products cannot match.

The technical debt that accumulates in multi-use-case products - where different features require different architectural decisions - is largely avoided when focus is maintained.

Third, marketing and positioning become exponentially more effective.

A company that can clearly articulate exactly what problem they solve, for whom, and why they're the best solution, can craft messaging that resonates deeply with their target audience.

This clarity translates into more efficient customer acquisition, stronger word-of-mouth growth, and better market positioning against competitors.

Historical Patterns in Technology Adoption

The technology industry provides numerous examples of companies that achieved dominance by initially focusing on one killer use case before expanding their scope.

These patterns reveal consistent principles about how focused solutions capture markets and create lasting competitive advantages.

Slack's transformation of workplace communication illustrates this principle perfectly.

While numerous communication tools existed before Slack's emergence, most tried to be everything to everyone - email replacement, project management, file sharing, and casual chat all rolled into one.

Slack identified that the core pain point wasn't the lack of communication tools, but the difficulty of maintaining context and continuity in team conversations.

By focusing exclusively on making team communication more organised and searchable, Slack created a solution so compelling that it became indispensable for millions of knowledge workers.

The key insight from Slack's success lies not in what they built, but in what they deliberately chose not to build in their early years.

They resisted the temptation to add project management features, robust file storage, or advanced workflow automation.

Instead, they perfected the core experience of team messaging, ensuring that their solution for this one use case was so superior that users couldn't imagine using anything else.

Similarly, Zoom's rise to dominance in video conferencing demonstrates the power of obsessive focus on solving one problem exceptionally well.

When Zoom entered the market, video conferencing solutions already existed from established players like Cisco, Microsoft, and Google.

However, these solutions treated video conferencing as one feature among many in broader communication suites.

Zoom recognised that the core pain point wasn't the availability of video calling, but the reliability and ease of use of video calls.

By focusing exclusively on making video calls that "just work" - with superior audio quality, reliable connections, and intuitive interfaces - Zoom created a solution that became essential for remote work.

Their obsessive focus on this single use case allowed them to optimise every aspect of the experience, from the underlying network protocols to the user interface design, in ways that companies with broader product portfolios could not match.

The Network Effects of Solving Critical Pain Points

When a product becomes essential for solving a specific pain point, it often triggers network effects that create additional barriers to competition.

These network effects emerge not from the product's breadth, but from its depth of penetration in solving a critical problem.

The pattern typically unfolds in predictable stages.

Initially, early adopters embrace the solution because it solves their specific problem better than alternatives.

As adoption grows within organisations or communities, the solution becomes embedded in workflows and processes.

This embedding creates switching costs that go beyond the product itself - users develop muscle memory, organisations build processes around the tool, and teams establish communication patterns that depend on the solution's specific features.

Eventually, the solution reaches a tipping point where it becomes the de facto standard for its use case.

At this point, network effects amplify its value: new users adopt it because everyone else is using it, vendors integrate with it because of its market position, and complementary tools are built around it.

This creates a self-reinforcing cycle that makes displacement extremely difficult, even for technically superior alternatives.

Notion's evolution provides a contemporary example of this phenomenon.

While many productivity tools attempt to combine note-taking, project management, and collaboration features, Notion initially focused on becoming essential for structured knowledge management.

By creating the best solution for teams that needed to organize and share complex information hierarchically, they established a beachhead that later enabled expansion into adjacent use cases.

The Competitive Dynamics of Focused Solutions

Markets tend to reward focused solutions with defensive moats that are difficult for competitors to cross.

These moats emerge from the accumulated advantages of deep specialisation rather than from patent protection or exclusive partnerships.

When a company becomes the definitive solution for a specific pain point, they often achieve what economists call "increasing returns to scale" in their market position.

Each new customer provides data that improves the solution, funding that enables further optimisation, and advocacy that drives additional adoption.

This creates a virtuous cycle where market leadership becomes self-reinforcing.

Competitors attempting to challenge a well-established, focused solution face a multi-dimensional disadvantage.

They must not only match the incumbent's technical capabilities - which represent years of focused development - but also overcome the switching costs, network effects, and brand association that the incumbent has built.

Most critically, they must do this while the incumbent continues to improve their solution with the benefit of market feedback and resources from their existing customer base.

The challenger's disadvantage becomes even more pronounced when considering the resource allocation dynamics.

While the challenger must spread their resources across customer acquisition, product development, and market education, the incumbent can focus primarily on product refinement and expansion, having already solved the initial problems of product-market fit and customer acquisition.

Organisational Implications of the Focus Strategy

Adopting a focus strategy requires fundamental changes in how organisations think about success, measurement, and resource allocation.

These changes often conflict with conventional business wisdom and require strong leadership to implement and maintain.

The most significant challenge lies in resisting the temptation to expand too quickly.

When a focused solution gains traction, stakeholders often pressure teams to broaden their scope to capture adjacent opportunities.

This pressure intensifies when competitors appear to be gaining ground by offering more comprehensive solutions.

However, premature expansion typically dilutes the very focus that created the initial success.

Successful implementation of a focus strategy requires developing organizational muscles that many companies lack.

Teams must become expert at saying no to good opportunities in order to pursue great ones.

They must resist the pressure to chase every customer request that pulls them away from their core use case.

Most importantly, they must maintain conviction in their strategy even when short-term metrics might suggest that a broader approach could yield faster growth.

The measurement systems within focused organisations must also evolve.

Traditional metrics like feature count, market coverage, or total addressable market become less relevant than deeper measures of customer dependence, usage intensity, and problem-solving effectiveness.

Organisations must develop new ways to measure whether they're becoming more essential to their users over time, rather than simply reaching more users.

The Paradox of Expansion Through Contraction

One of the most counterintuitive aspects of the focus strategy is that the path to broad market impact often runs through narrow market dominance.

Companies that eventually become platforms or ecosystems almost always begin by being indispensable for one specific use case.

This paradox resolves when we consider how trust and credibility are built in markets.

Users and organisations are more likely to depend on a company for additional needs when that company has proven they can solve one problem exceptionally well.

The credibility earned through focused excellence becomes a platform for expansion that is much more stable than the credibility attempted through immediate breadth.

Amazon's evolution from online bookstore to everything store exemplifies this principle.

By becoming the definitive solution for buying books online - solving the specific pain point of book discovery and delivery better than anyone else - Amazon built the operational capabilities, customer trust, and market position that enabled their expansion into other product categories.

Had they attempted to become an everything store immediately, they likely would have failed to achieve excellence in any category.

The expansion timing becomes critical in this strategy.

Companies must expand only after achieving true dominance in their initial use case, and even then, expansion should typically target adjacent pain points for the same user base rather than the same pain point for different user bases.

This approach leverages the trust and understanding built through the initial relationship while maintaining the focus that created the competitive advantage.

Conclusion: The Strategic Imperative of Essential Solutions

In an economy where attention is scarce and switching costs are often low, becoming essential represents the most sustainable form of competitive advantage.

The companies that achieve lasting success are rarely those that do many things adequately, but rather those that do one thing so well that users cannot imagine alternatives.

The implications extend beyond product strategy to fundamental questions about how organisations create value in the modern economy.

As markets become more efficient and users become more sophisticated, the premium for excellence continues to increase while the tolerance for mediocrity decreases.

Companies that spread their efforts across multiple mediocre solutions find themselves competing primarily on price and convenience - a race to the bottom that benefits neither businesses nor users.

The focus strategy requires courage - the courage to say no to seemingly attractive opportunities, to ignore competitive moves that seem threatening in the short term, and to maintain conviction in a narrow vision when broader approaches might seem safer.

However, for organisations willing to embrace this approach, the rewards compound over time in ways that broad-spectrum strategies cannot match.

The most successful companies of the coming decades will likely be those that recognise this fundamental truth: in a world full of options, being essential for one important thing beats being optional for many things.

The path to broad impact runs through narrow excellence, and the companies that master this paradox will be the ones that define the future of their industries.

Source : Rajesh Sehgal, Complexity is Killing your Startup

References

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1984). Choices, values, and frames. American Psychologist, 39(4), 341-350.

Schwartz, B. (2004). The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less. New York: HarperCollins.

Arthur, W. B. (1989). Competing technologies, increasing returns, and lock-in by historical events. The Economic Journal, 99(394), 116-131.

Christensen, C. M. (1997). The Innovator's Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Parker, G. G., Van Alstyne, M. W., & Choudary, S. P. (2016). Platform Revolution: How Networked Markets Are Transforming the Economy and How to Make Them Work for You. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Eisenmann, T., Parker, G., & Van Alstyne, M. (2006). Strategies for two-sided markets. Harvard Business Review, 84(10), 92-101.

Shapiro, C., & Varian, H. R. (1999). Information Rules: A Strategic Guide to the Network Economy. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

Moore, G. A. (2014). Crossing the Chasm: Marketing and Selling Disruptive Products to Mainstream Customers. New York: HarperBusiness.

Ries, E. (2011). The Lean Startup: How Today's Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses. New York: Crown Business.

✍️ Why I Wrote This

I’m endlessly fascinated by startups and the emotional rollercoaster that begins the moment a founder has that epiphany - the “aha!” moment 💡 where a problem grips them so tightly they feel compelled to solve it.

As a recovering Founder and Co-Founder myself - and someone who now supports startup founders and leadership teams across the globe 🌍 - I’ve seen something intriguing: the way a person approaches decision-making, risk, and intuition often varies dramatically depending on their age, experience, or both.

That divergence becomes especially clear when tackling the issue in this piece - not being able to focus and keep digging until you can confirm the killer use case that will allow you to repeat across multiple customers. Too many founders try to hedge and cast their net too wide rather than continuing to dig and dig until they hit the rich seam of alignment with their ideal customer pain point.

In working with founders, I’ve learned that the best founders face into this reality of traction and valid alignment of their strategy. Choose your destiny. More on this soon.

💥 If you’ve been here before, what did you do? How did you get there and what was your learning? Let’s talk in the comments

🎧 Let’s Stay Connected

If you enjoyed this piece, please subscribe here on SubStack and consider following my podcast, The G&T Sessions - where I dive deeper into the minds of remarkable founders, creators, and change makers.

🎙 Listen + subscribe → https://www.linktr.ee/thegtsessions

(For deeper dives into the psychology of founders.)

You can also follow me on X → https://www.x.com/andrewjturner

Ciao for now 👋

– Andrew