TL;DR: Sergei Korolev, the anonymous architect of the Soviet space program, beat better-funded American rivals by making faster decisions with incomplete data, ruthlessly prioritising speed over perfection, and building a team that could execute under extreme constraints.

For software founders in 2025 facing decisions about customers, revenue, and capital, Korolev’s lessons are clear: constraint breeds innovation, speed trumps resources, and the founder who ships first often wins - even against giants.

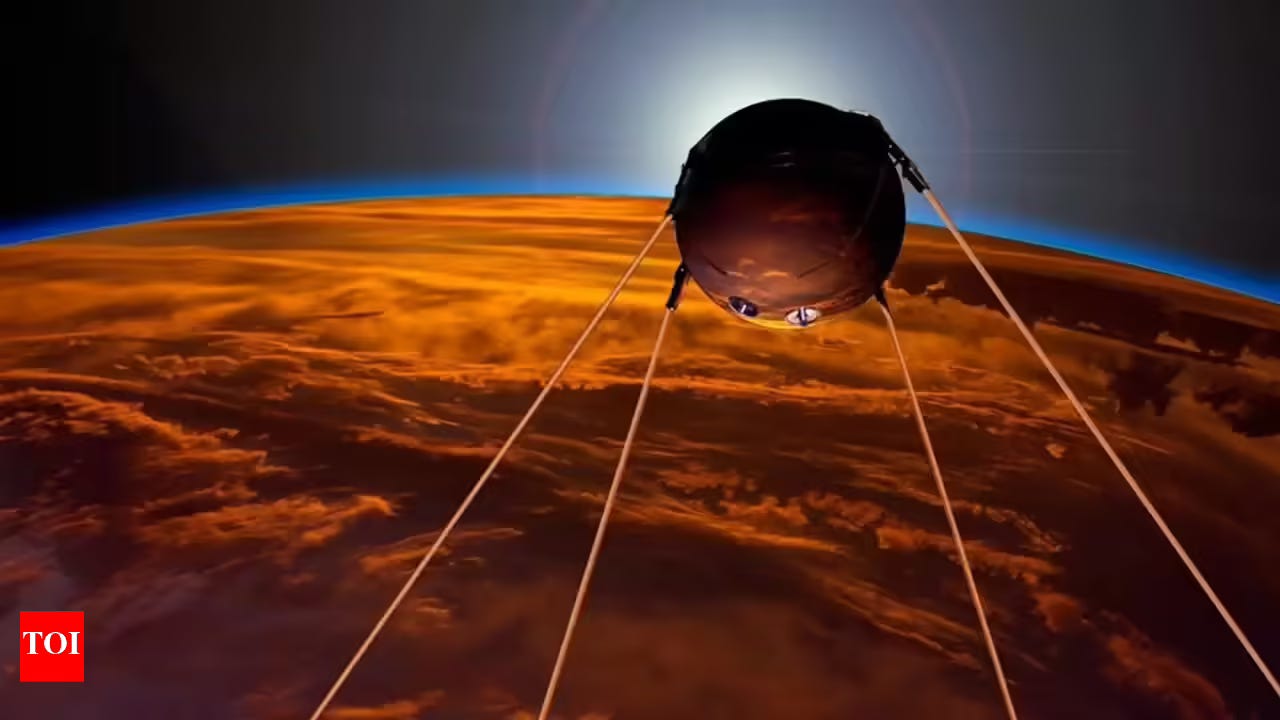

His name was a state secret.

His face never appeared in newspapers.

When Sputnik launched in 1957, shocking the world and humiliating America, the man who built it remained unknown - identified only as “Chief Designer.”

Sergei Korolev died in 1966 without public recognition.

Yet this invisible engineer had accomplished what seemed impossible:

He beat the United States to every major milestone of the Space Race despite having a fraction of NASA’s budget, inferior technology, and working under a regime that had imprisoned him in the Gulag just years earlier.

For software founders in 2025, Korolev’s story isn’t just inspirational - it’s instructional.

He faced the same fundamental challenge you face:

How do you win against better-funded competitors when you have limited resources, uncertain technology, and a ticking clock?

The answer isn’t what most founders expect.

Source : The Times of India

The Power of Constraint: Building Sputnik on a Shoestring

When Korolev proposed launching the first satellite, the Soviet leadership was skeptical.

They wanted intercontinental ballistic missiles, not “space toys.”

Korolev had limited budget, limited time, and leadership that didn’t understand his vision.

Sound familiar?

Instead of waiting for perfect conditions, Korolev made a decision that changed history:

He would build the simplest possible satellite that could actually work.

While American engineers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory designed sophisticated satellites packed with instruments, Korolev built a 184-pound polished sphere with a radio transmitter.

That’s it.

Sputnik was so simple it seemed primitive.

But it worked.

And it launched first.

The founder lesson:

Your competitors with more funding will build more features.

They’ll have more sophisticated technology.

They’ll have better branding.

None of that matters if you ship first and prove the concept.

The market rewards working products, not perfect ones.

Too many founders wait for the “right” product-market fit, the “right” feature set, the “right” market conditions.

Korolev understood that in a race, the first mover advantage often compounds.

While America was planning, he was launching.

Decision Velocity: Why Korolev Beat NASA

The United States had more money, better computers, superior manufacturing, and access to German rocket scientists (including Wernher von Braun himself).

On paper, there was no competition.

But Korolev had something more valuable than resources:

Decision velocity.

In the Soviet system, once Korolev convinced Khrushchev, he could move fast.

No endless committee meetings.

No layers of approval.

No design-by-democracy.

He made technical decisions swiftly, often with incomplete data, and his team executed immediately.

When the Americans discovered Soviet progress on Sputnik, they accelerated their own program.

The U.S. Naval Research Laboratory’s Vanguard satellite was more sophisticated, more advanced, better engineered.

It exploded on the launch pad on live television in December 1957.

Meanwhile, Sputnik II - carrying the dog Laika - had already launched a month earlier.

The Founder lesson:

In competitive markets, the velocity of your decision-making is a competitive advantage.

Your VP of Sales wants more data before choosing a customer segment.

Your CTO wants to rebuild the architecture before scaling.

Your investors want another quarter of metrics before committing to Series A.

Meanwhile, your competitor ships, learns, and iterates.

Perfect decisions executed slowly lose to good decisions executed fast.

The founder who can compress the decision cycle - research quickly, decide firmly, execute immediately - creates compounding advantages that resources alone can’t match.

Ruthless Prioritisation: What to Build When You Can’t Build Everything

Korolev wanted to send humans to the Moon, build space stations, and create reusable spacecraft.

He had plans for all of it.

But he had limited resources and the American competitor was moving fast.

So he made a choice that defined the entire Space Race:

Focus exclusively on being first at every major milestone, even if it meant cutting corners on everything else.

First satellite.

First animal in space.

First human in space.

First spacewalk.

First woman in space.

First multi-person crew.

First space station.

Each victory was achieved by asking:

“What’s the minimum we need to accomplish this specific goal before the Americans?”

Everything else was cut.

Safety margins were reduced.

Redundancies were eliminated.

Creature comforts were sacrificed.

When Yuri Gagarin launched in Vostok 1, his capsule had no abort system, minimal life support, and couldn’t change its trajectory.

American engineers would have considered it criminally reckless.

But it worked.

And it launched three weeks before Alan Shepard’s suborbital flight.

The Founder lesson:

You cannot be everything to everyone.

You cannot build every feature, serve every customer segment, or pursue every revenue opportunity simultaneously.

Strategy is subtraction.

What will you NOT do, even though it’s possible?

Which customers will you ignore, even though they have budget?

Which features will you skip, even though users request them?

The founder who tries to compete on every dimension loses to the founder who picks one dimension, dominates it, and moves to the next battle after winning.

Your job isn’t to build the best possible product.

Your job is to win your specific market before someone else does.

Everything else is distraction.

Managing Uncertainty: Making Billion-Dollar Bets with Incomplete Data

Korolev never had perfect information.

Soviet intelligence on American capabilities was fragmentary.

Component reliability was uncertain.

Technologies had to be invented as they went.

Every major decision was a calculated gamble.

The decision to send Gagarin into space was made knowing:

The re-entry heat shield might fail (it didn’t)

The retro-rockets might malfunction (they did, but Gagarin survived anyway)

The Americans were probably months away from their own attempt

If anything went catastrophically wrong, Korolev would likely be executed

He sent Gagarin anyway.

The Founder lesson:

If you wait for certainty, you wait forever.

The market doesn’t reward thorough analysis - it rewards correct-enough decisions made fast enough to matter.

Your customer acquisition strategy won’t have perfect data.

Your pricing model will require assumptions about willingness to pay.

Your capital raise will demand projections based on incomplete market information.

Make the decision anyway.

Build in contingencies, yes.

Plan for failure modes, absolutely.

But recognise that the founder who moves at 70% confidence beats the founder who waits for 95% confidence.

In Korolev’s world, the cost of a wrong decision could be death.

In yours, it’s probably a pivot.

So why are you waiting?

Building Teams Under Pressure: The Korolev Method

Korolev’s team worked under impossible conditions.

They had survived Stalin’s purges (Korolev himself spent years in the Gulag).

They worked in secret.

They faced constant pressure from leadership who didn’t understand the technology.

Resources were scarce.

Failures could mean imprisonment or worse.

Yet Korolev built a team that achieved the impossible repeatedly.

How?

First: He protected his team from political pressure.

When things went wrong (and they often did), Korolev absorbed the criticism from above.

His engineers could focus on solving technical problems, not managing political fallout.

Second: He gave them clear missions, not detailed instructions.

“Get a satellite into orbit by October.”

“Put a human in space before the Americans.”

His team had autonomy in execution.

Third: He hired for resourcefulness over credentials.

Many of his best engineers came from unconventional backgrounds.

What mattered wasn’t their degrees - it was their ability to solve novel problems with limited resources.

The Founder lesson:

Your early team will make or break you.

Not because of their technical skills (though those matter), but because of their ability to execute under uncertainty, adapt when plans change, and ship despite imperfect conditions.

Stop hiring for “culture fit” and start hiring for “culture add.”

Stop looking for people who’ve done the exact job before and start looking for people who can figure out jobs that have never existed.

And most critically:

Protect your team from noise.

Investors asking for unnecessary updates.

Customers requesting tangential features.

Board members questioning the strategy.

Your job as founder is to create clarity and space for your team to execute.

The Revenue Model Decision: Korolev’s Hidden Leverage

Here’s what most people miss about Korolev’s success:

He didn’t just build rockets - he built a business model that ensured continuous funding.

The Soviet military wanted ICBMs.

Korolev wanted space exploration.

He didn’t fight this tension - he leveraged it.

Every rocket he designed had dual use:

Military payload delivery AND space exploration.

His R-7 rocket that launched Sputnik was also the USSR’s first ICBM.

His designs for crewed spacecraft incorporated reconnaissance capabilities.

By aligning his space ambitions with military priorities, Korolev ensured his program was “revenue generating” (in Soviet terms: strategically essential and continuously funded).

The Founder lesson:

The best revenue model isn’t the one that maximises short-term cash - it’s the one that aligns your product development with a sustainable source of customer value.

Too many founders build what they want to build, then retrofit a revenue model.

Korolev did the reverse:

He identified who had the budget and the strategic imperative (the military), then designed his product to serve their needs while achieving his own objectives.

Your enterprise customers want ROI and risk reduction.

Your SMB customers want ease of use and quick wins.

Your consumer users want status or entertainment.

Design your product and revenue model to deliver what they actually value, not what you think they should value.

The founder who aligns product roadmap with customer budget priorities never struggles with revenue.

Capital Strategy: When to Raise and How Much

Korolev’s relationship with Soviet leadership was essentially a continuous fundraising process.

After each success, he had to pitch the next, bigger goal.

After each failure, he had to convince them not to shut down the program.

His capital strategy had three elements:

1. Raise from a position of strength: After Sputnik’s success, Korolev immediately proposed the next mission (Sputnik II with Laika). He used momentum to secure resources for bigger bets.

2. Show traction before asking for scale funding: He didn’t ask for Moon mission budgets before proving he could launch satellites. Each success earned the right to attempt something bigger.

3. Time raises around competitive pressure: When American progress accelerated, Korolev used the threat of losing the race to unlock additional resources. External competition became his leverage.

The Founder lesson:

The best time to raise capital is right after a major win, when you have momentum and leverage.

The worst time is when you’re desperate and out of options.

Build your funding strategy like Korolev built his space program:

Start with a small bet that proves the concept (angel/pre-seed)

Use that success to unlock resources for the next stage (seed)

Show traction at each level before asking for scale capital (Series A+)

Use competitive dynamics to improve terms (multiple term sheets)

And critically:

Raise enough to reach the next major milestone, not just to extend runway.

Investors fund momentum, not survival.

Iteration Under Fire: The Vostok Evolution

The Vostok spacecraft that carried Gagarin was version 1 of a design that went through multiple iterations.

Each flight revealed problems.

Each problem was fixed rapidly.

The gap between flights was measured in weeks, not years.

When Vostok 1’s re-entry went wrong (the service module didn’t separate cleanly), Korolev’s team identified the issue, redesigned the separation mechanism, and launched Vostok 2 four months later.

Compare this to the American approach:

Extensive ground testing, simulation, and validation before each mission.

More thorough, yes.

But slower.

The Founder lesson:

The fastest way to learn is to ship, observe, and iterate.

Not to plan, simulate, and perfect.

Your customer acquisition strategy won’t be right on version 1.

Ship it anyway and measure what happens.

Your pricing model will need adjustment.

Launch it anyway and track conversion rates.

Your product positioning will evolve.

Test it in market and iterate based on real feedback.

The military has a saying:

“No plan survives contact with the enemy.”

In startups:

No strategy survives contact with customers.

So make contact faster.

Ship the MVP.

Launch the campaign.

Start the outbound.

Test the pricing.

You’ll learn more from one week in market than six months of planning.

The Korolev Doctrine: Winning Against Giants

Let’s synthesise Korolev’s approach into a framework for software founders competing against better-funded rivals:

1. Simplify ruthlessly.

Cut everything that doesn’t directly serve your immediate objective.

Ship the minimum that works.

2. Decide fast.

Compress your decision cycle.

Research quickly, decide firmly, execute immediately.

3. Prioritise being first over being best.

Capture the milestone before competitors, even if your solution isn’t perfect.

4. Make bets with incomplete data.

70% confidence is enough.

Waiting for certainty means losing to someone who moved faster.

5. Align your product with customer budgets.

Build what people will actually pay for, not what you think they should want.

6. Raise from strength.

Use momentum and traction to improve terms and timing.

7. Iterate in public.

Ship, learn, fix, repeat.

Market feedback beats internal planning.

8. Protect your team’s focus.

Absorb the noise so they can execute.

This isn’t about cutting corners recklessly.

Korolev was rigorous about what mattered (orbital mechanics, life support, heat shields).

But he was ruthless about cutting what didn’t (comfort, redundancy, lengthy validation processes).

The question for you:

What are you being rigorous about that doesn’t actually matter?

What “best practices” are you following that slow you down without improving outcomes?

The Hidden Cost of Perfection

Here’s the uncomfortable truth:

Korolev’s approach was dangerous.

Cosmonauts died.

Rockets exploded.

Corners were cut that shouldn’t have been.

So should you copy his methods exactly?

Of course not

Source : Wikipedia

But recognise the opposite extreme:

FFounders who never ship because the product isn’t perfect, never commit to a customer segment because the data isn’t complete, never raise capital because the metrics aren’t ideal.

There’s a spectrum between reckless speed and paralytic perfectionism.

Most founders are too far toward perfection.

Korolev was too far toward speed.

The optimal point is probably somewhere in between - but closer to Korolev than most founders are comfortable admitting.

The market doesn’t reward perfect products that ship late.

It rewards good-enough products that ship first and iterate fast.

What Would Korolev Do?

You’re facing a decision right now.

Maybe it’s:

Which customer segment to focus on

Whether to raise capital or push for profitability

What pricing model to adopt

Which features to cut from the roadmap

Whether to pivot or persevere

You don’t have perfect information.

You won’t get perfect information.

Your competitors are moving.

What would Korolev do?

He’d identify the minimum threshold for success.

He’d make the call with available data.

He’d commit the team fully.

And he’d ship before you finished your analysis.

Not because he was reckless.

Because he understood that in competitive markets, the cost of delay often exceeds the cost of imperfection.

Your job isn’t to make perfect decisions.

It’s to make good-enough decisions fast enough to win.

The Chief Designer would approve.

The Foundarity Sprint: Where Decisions Get Made

September’s Foundarity Sprint has wrapped, and the results speak for themselves.

Founders who joined didn’t just talk about making decisions - they made them.

Customer segments were chosen.

Revenue models were locked in.

Capital strategies were crystallised.

The November Sprint is now open: November 7-9, 2025.

Three days.

One focus: Getting absolute clarity on the big decisions that will define your next 12 months.

This isn’t a course.

It’s not a workshop.

It’s a private design lab where selected founders, investors, and guest speakers work through the exact decisions you’re facing:

Who is your customer?

Not “who could be” - who IS)

What revenue model actually works for your market?

(Not in theory — in practice)

When do you raise, and how much?

(Based on your specific traction and goals)

What do you ship first?

(And what do you cut, even if it hurts)

The founders who joined September’s sprint made more progress in three days than they had in the previous three months.

Not because we gave them answers, but because we created the conditions for clarity.

Here’s what we’re not doing:

We’re not teaching you generic startup frameworks

We’re not running feel-good brainstorming sessions

We’re not letting you leave without decisions made

Here’s what we are doing:

Forcing the hard conversations you’ve been avoiding

Bringing in operators who’ve made these exact decisions at scale

Creating accountability so decisions stick

Building a community of founders who execute, not just plan

The question is:

Are you still planning, or are you ready to decide?

Korolev didn’t wait for perfect information.

He didn’t convene another committee meeting.

He made the call and launched.

What are you launching?

Join the FREE Foundarity Community: https://www.bit.ly/JoinFoundarityCommunity

Get access to frameworks, templates, and a community of founders who ship.

Book a Clarity Call: Ready to stop planning and start deciding?

https://scheduler.zoom.us/atfoundarity/clarity-call

Let’s talk about whether the November Sprint is right for you.

No sales pitch.

Just a real conversation about the decisions you’re facing.

The Chief Designer didn’t achieve the impossible by thinking about it longer.

Neither will you.

Curated References

Books

“Korolev: How One Man Masterminded the Soviet Drive to Beat America to the Moon” by James Harford (1997)

The definitive English-language biography of Korolev, based on newly opened Soviet archives.“Challenge to Apollo: The Soviet Union and the Space Race, 1945-1974” by Asif Siddiqi (2000)

Comprehensive technical and political history of the Soviet space program from NASA’s official historian.“Red Moon Rising: Sputnik and the Hidden Rivals That Ignited the Space Age” by Matthew Brzezinski (2007)

Narrative account of the Sputnik launch and the personalities behind it.

Academic Articles

“The Chief Designer: Sergei Korolev and the Race to the Moon” — Air & Space Magazine, Smithsonian Institution

Accessible overview of Korolev’s career and achievements.“Soviet Space Culture: Cosmic Enthusiasm in Socialist Societies” edited by Eva Maurer et al. (2011)

Academic analysis of how the Soviet space program shaped culture and propaganda.

Documentaries

“Red Files: Secrets of the Russian Space Program” (BBC, 1999)

Interviews with Soviet engineers and cosmonauts, declassified footage.“Cosmonaut: How Russia Won the Space Race” (2014)

British documentary examining Soviet achievements through modern lens.

Online Resources

NASA History Division: Soviet Space Program

https://history.nasa.gov/sputnik/

Declassified documents and analysis from American perspective.RussianSpaceWeb.com

http://www.russianspaceweb.com/korolev.html

Detailed technical information on Korolev’s designs and missions.

Primary Sources

Korolev’s Design Bureau Archives (partially digitised)

Technical specifications and mission reports, available through Russian state archives.